During conversations with the public during workshops or with people who contact me via the Internet, I noticed that many people believe that an omnivorous but local diet is more environmentally friendly than a living food diet (raw plant-based) which often favors imported fruits and vegetables from outside our regions. This is the purpose of this article: to determine, with reliable sources, the ecological footprint of these two types of diets, local omnivore vs. raw vegan, and to determine if they are compatible with a “sustainable” future for our species.

One of the principles of a living food diet is to listen to your cravings as long as they guide you towards raw plants. Because the human body can identify (in the case of raw plants only) the nutrient content of what it is given, it can then guide us towards the fruits and vegetables that will heal us, fill our deficiencies, or simply nourish us best. By listening to one’s instinct, it is complicated (for now, as you will see at the end of this article) for a raw vegan to also be local under our latitudes (I am speaking for central France and those further north). This is why a raw vegan may consume bananas, dates, mangoes, avocados, pineapples, ginger, turmeric, cashews, Brazil nuts, etc., for a significant part of their meals. Especially at the beginning when they have deficiencies to fill, then this consumption of exotic fruits decreases.

As I have already explained in the articles “Why did I change my diet?”, “Eating Living?” and “Cleanses, the Keystone”, my opinion, supported by experience, is that the diet best suited to humans is a predominantly plant-based and living diet (i.e., raw plant-based).

If this viewpoint seems contradictory to you given that many centenarians have eaten “everything” during their lives, then I suggest you read this other article: “What is hygienism?”, and you will then see that the parameter “diet”, even if it is important, is not the only one. Indeed, a life in pure fresh air, without stress, with periods of fasting or restrictions (war or poor harvest) and with physical activity spares many diseases. The lives of all these centenarians are therefore not at all in contradiction with the principles of living food. And then, who tells you that under optimal conditions on all levels we wouldn’t live to 140 years?

Diet and Carbon Dioxide

But let’s get back to our topic and, despite these considerations, let us first calculate the GHG (Greenhouse Gas, sometimes noted CO2e for “carbon dioxide and equivalents”) balance of a local omnivore vs. a raw vegan.

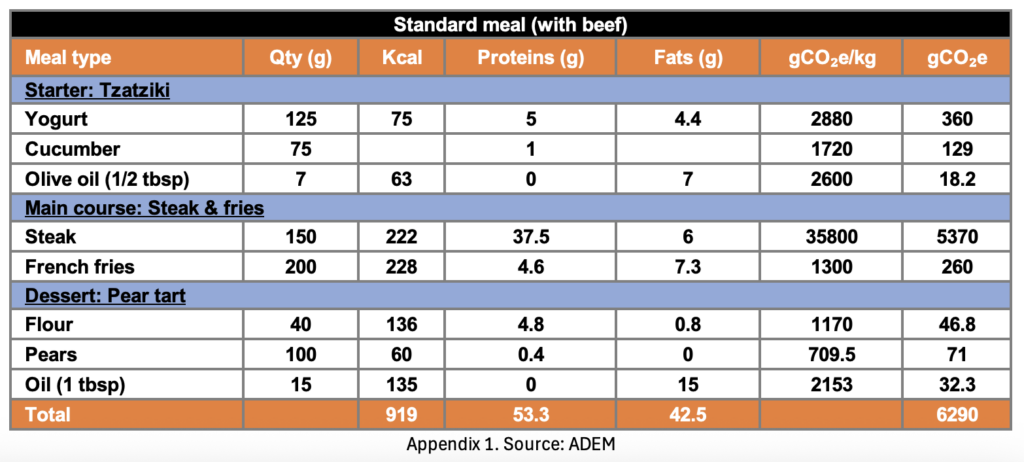

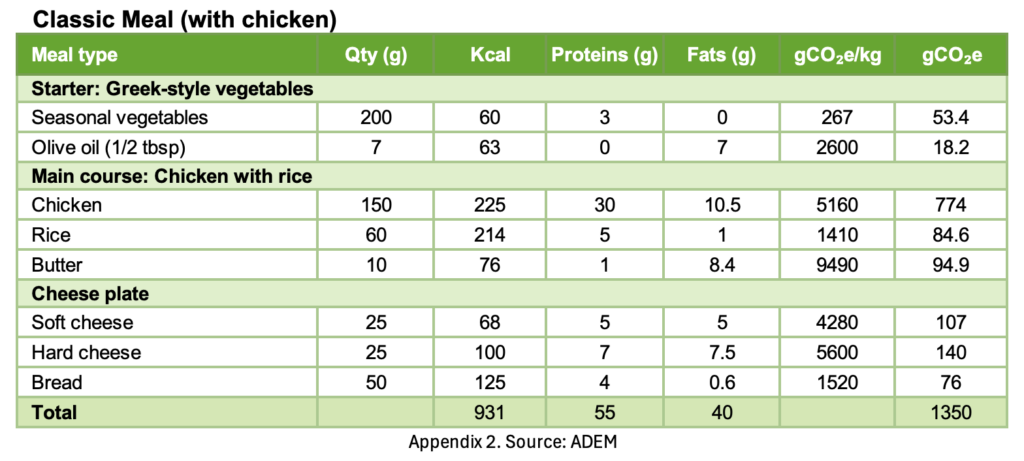

According to the ADEME (Agency for the Environment and Energy Management), the fact that it is under the supervision of a ministry guarantees that there is no bias towards vegans!), an omnivore consuming only natural products within a 200 km radius emits for:

- a meal with beef: 6290 g of CO2e (see appendix 1)

- a meal with poultry: 1350 g of CO2e (see appendix 2)

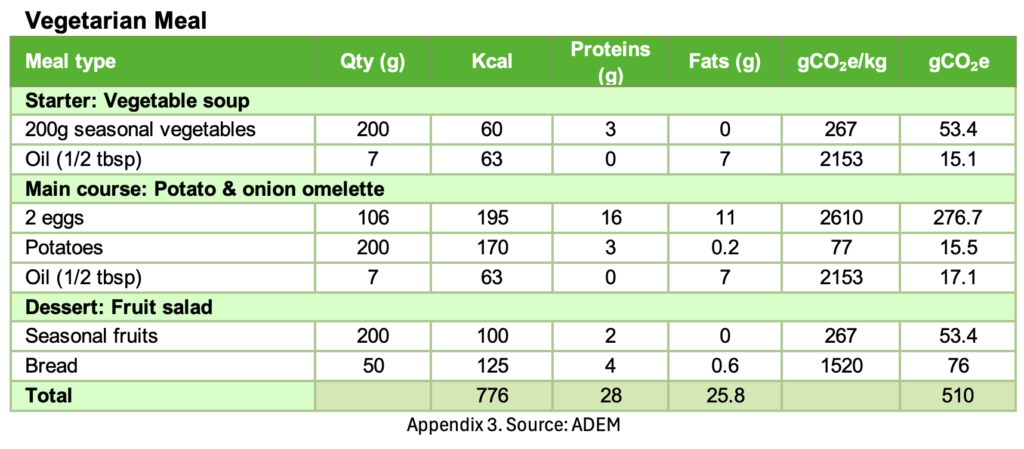

- a vegetarian meal: 510 g of CO2e (see appendix 3)

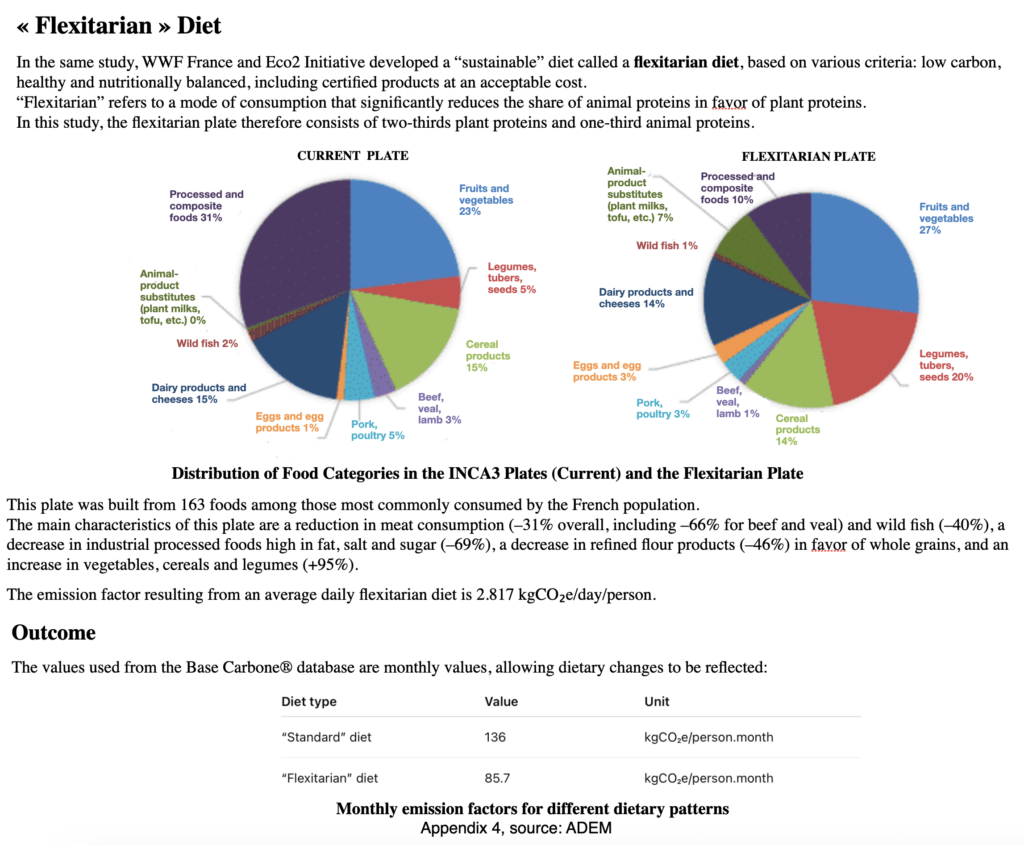

According to this agency, the average GHG balance of the diet is currently 4.5 kg of CO2e per day per person. Official recommendations advocate for a more moderate, reasonable, and local diet (less than 200 km) called “flexitarian” (-31% meat, -40% wild fish, -69% processed industrial products, -46% refined flours, +95% vegetables, grains, and legumes) which would yield a balance of 2.8 kg of CO2e per day per person. This is therefore what can be achieved better from an omnivorous diet in terms of GHG balance.

As for the “degrowth” advocates who would argue that one can live the old-fashioned way: feeding on grains, legumes (in this regard, read the article addressing the issue of starches) and poultry, know that according to the documentary film Cowspiracy and several independent studies conducted by specialists in agroecology and permaculture, they arrive at more or less the same conclusion (which all those who have tried to live in autarky will agree with): It takes an average of 700m2 to feed a vegan compared to 3500m2 for an omnivore who would consume very few animal products, which is 5 times more space. It should also not be forgotten that these additional spaces required for the omnivore are deforested to allow for grazing or to sow grains on soils depleted by plowing, monoculture, fertilizers, and pesticides. A source of pollution that adds to that of GHGs.

A first conclusion must be drawn regarding the GHG balance (per day and per person) related to diet alone:

- Currently, an average French person emits 4.5 kg of CO2e.

- A flexitarian local French person (concerned about their health, the planet but omnivorous) consuming only foods produced within a 200 km radius emits 2.8 kg of CO2e (see appendix 4).

- An individual (if they exist) who is omnivorous and lives in autarky with organic production and consumes very few animal products would be responsible for a negligible share of GHG emissions but would need at least 3500 m2 of land.

Now let’s assess the balance for a raw vegan:

According to the software developed by eco2 initiative (This link leads to a website in French. To read it in English or another language, simply copy the URL and paste it into Google Translate https://translate.google.com/?sl=fr&tl=it&op=translate) in collaboration with ADEME, a raw vegan who would consume the following typical menu (2050 Kcal) in their day:

- 200g of avocado outside Europe

- 200g of local carrots (less than 200 km)

- 40g of cashews outside Europe

- 50g of olives from Europe and the Mediterranean

- 50g of vegetables outside Europe

- 60g of almonds Europe and Mediterranean

- 250g of bananas outside Europe

- 500g of local apples

- 300g of fruits outside Europe

- 25g of olive oil from France

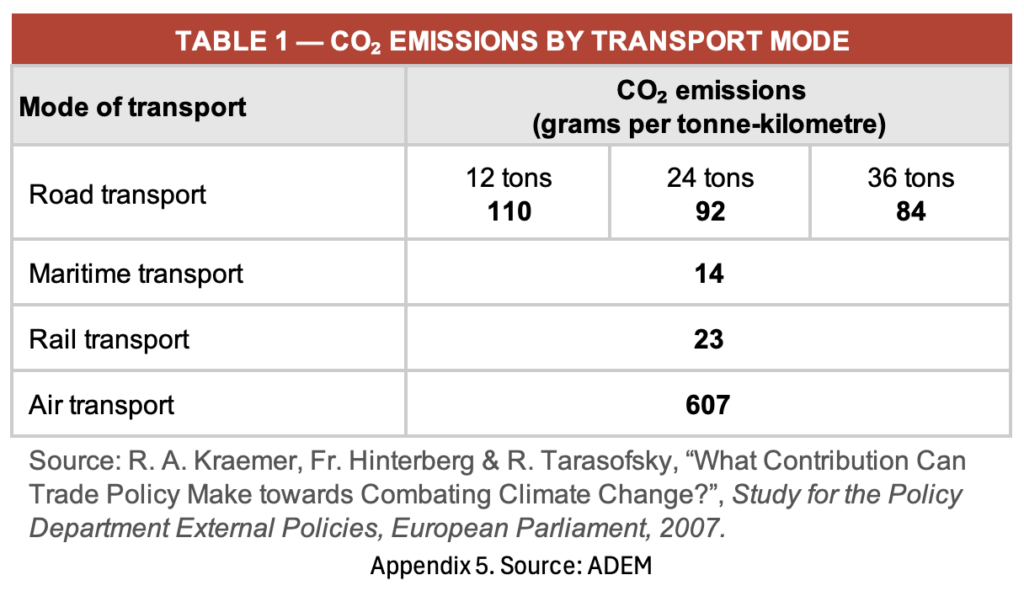

would be responsible for an emission of 1.9 kg of CO2e per day, which is 1.1 kg less than a flexitarian French person (over a year, the difference is equivalent to a flight from Paris to New York) and 2.6 kg less than an average omnivorous French person (over a year, the difference is equivalent to 2.5 flights from Paris to New York). However, a nuance must be made, if exotic fruits and vegetables are imported by air from a long distance (like 10,000 km, this merchandise is recognized by its very high price), according to Appendix 5, it costs 6 kg of CO2e per kilo of food compared to only 140g of CO2e if the same food arrives by boat. A raw vegan who consumes fruits and vegetables imported by air can quickly ruin their CO2e balance, which becomes equivalent to or higher than that of an average omnivore. Moral of the story: any dietary effort to reduce your GHG emissions is quickly negated if you use air travel.

Finally, a significant parameter must be taken into account because all the previous calculations have taken as a reference a consumption of about 2000 Kcal per day per person. However, traditional food with cereals, sugars, meat, and dairy products is addictive and the obesity epidemic observable in France (as elsewhere) shows that omnivores, on average, do not limit themselves to only 2000 Kcal per day. Conversely, when transitioning to a living food diet, one realizes that caloric needs are divided by 1.5 or even 2 for the same physical expenditure (this is for several reasons: better assimilation, optimized digestion, and the cells of the body bathing in a healthier environment have a longer lifespan).

Taking this correction into account, it can be deduced that a raw vegan avoiding consuming products imported by air emits on average 1.2 kg of CO2e per day, which is much less than anyone, except for those living in self-sufficiency.

A second conclusion is necessary:

- A raw vegan who is not concerned about the origin of their basket does not emit more GHG than the average French person.

- A raw vegan who has reduced their caloric needs but is keen to eat according to their desires while keeping an eye on the origin of their basket emits less GHG than anyone, except for a person living in self-sufficiency or growing a significant part of their food themselves.

This conclusion is not surprising for anyone observing the traffic related to livestock in the countryside. Moreover, according to the documentary Cowspiracy and according to the Worldwatch Institute (read the article from Indépendent) : cattle production produces more GHG than all transportation combined and livestock would, according to new estimates, be responsible not for 18% of GHG globally but for 51%.

As we will see in the rest of this article, the GHG that are partly responsible for the rise in average temperatures on our planet should they really capture all our attention? Even if we modify the concentration of certain gases in the atmosphere, we cannot overlook the damage caused by cereal crops dedicated to livestock (soil erosion, use of fertilizers and pesticides) and pastures (soil and water pollution) leading to deforestation and loss of biodiversity.

Explanation: still according to the documentary Cowspiracy, according to the Worldwatch Institute and according to various increasingly numerous sources, it appears that: 45% of the land used by humans is reserved for livestock.

- 91% of the deforestation of the Amazon rainforest is related to livestock.

- 53% of the freshwater extracted from the environment is used for livestock compared to 5% for our own consumption.

- Livestock is responsible for dead zones in the ocean threatening vast coastal areas (read the article).

Let’s continue with the absurd figures (madness?) :

- Only 4% of mammals on Earth are wild, all the others are livestock animals (read the article).

- There are 70 billion farm animals.

- Cows alone consume 62 million tons of cereals per day compared to 9.5 million for humans. 3 kg of cereals are used to produce 1 kg of animal product and each kilo of animal product contains half the calories found in 1kg of cereals…

- Cattle waste, which represents 130 times that of all humans, is spread in nature without septic tanks and is responsible for numerous and serious sources of pollution (read the article from Greenpeace).

- 60 billion land animals and 1000 billion marine animals are killed each year for our consumption.

In summary, a vegan saves:

- 1.8 tons of CO2e per year (if they do not consume air-imported foods)

- 4160 liters of water per day

- 20 kilos of cereals (produced with a lot of fertilizers and pesticides) per day

- 2.8 m2 of forests per day

- 1 animal life per day

- his life from many diseases whose therapies pollute our environment a little more

- to our planet many sources of pollution much more serious than GHGs…

To conclude this article, let’s look at the arguments made against veganism:

- Trees to produce fruits also consume a lot of water! They would even consume several hundred liters of water per day when it’s hot!

It’s forgetting a bit too quickly all the benefits that trees bring. Let’s mention a few: they prevent soil erosion and retain almost all rainwater (forest soils form a gigantic reservoir), they promote cloud formation (without them, no rain far from the coasts), they cool the climate (read the article, this link leads to a website in French. To read it in English or another language, simply copy the URL and paste it into Google Translate https://translate.google.com/?sl=fr&tl=it&op=translate) purify the air, increase biodiversity, enrich the soil, produce oxygen, capture CO2, and offer multiple services. Moreover, it has been discovered that half of the water taken up by trees is released directly into the environment. Conclusion: the GHG balance of a raw vegan could still be revised downwards if we took into account all the benefits that trees provide.

If we are truly frugivores, then why can’t we feed ourselves with what nature offers us locally?

Fabrice Desjours in his book “Forest Gardens” explains to us why the flora in Europe is so poor despite its temperate climate:

« In this case, harvesting would serve a dual purpose: containing the spread of bamboo and feeding you, since this giant, forest-forming grass fully deserves its place in a forest garden.

Furthermore, what would we eat without our imported plants? Apples, pears, peaches, apricots, tomatoes, cereals, melons, citrus fruits, chickpeas, potatoes, corn, watermelons, zucchinis, eggplants, squashes, peppers come from every corner of the world — and even the chestnut tree, native to Europe but which disappeared from France after the ice ages, was brought back from southern Europe through human migrations.

Let’s take advantage of this discovery to go back in time and learn how many plants used in a forest garden existed in Europe before the Quaternary glaciations, a period during which glaciers sometimes covered the land all the way down to Lyon.

For the flora of the Old Continent, the glaciations had disastrous consequences, unlike what happened in Asia or North America where relief and geography allowed vegetation to retreat further south during the advance of the glaciers. In Europe, between the insurmountable barrier of the Mediterranean and the great transverse mountain chains, migrating plant species collided with the Alps, Carpathians and Pyrenees.

The number of species lost — even entire botanical families — was considerable: bamboos, Symplocos, Nyssa, Lauraceae, Zelkova, Sciadopitys, hardy palms, and thousands of other plants once grew naturally in our regions! Many of the so-called “exotic” plants we now introduce into our gardens actually existed in France before the Quaternary and are easily found in the fossil record.

Ultimately, a forest garden is simply about reintroducing into Europe species and families that once existed but had disappeared… »

Source : Jardins-forêt, Fabrice Desjours

For the author, the solution lies in exploiting the wealth and global diversity of fruit species adapted to our temperate climate that could provide a whole range of fruits allowing raw vegans to also be locavores. This is not just a fanciful theory (see appendix 6) but indeed reality, as can be verified in wooded gardens that have existed for decades in England, Belgium, the Netherlands (see their site), Scotland, and also in France (see the gourmet forest of Châlon-sur-Saône, this link leads to a website in French. To read it in English or another language, simply copy the URL and paste it into Google Translate https://translate.google.com/?sl=fr&tl=it&op=translate).

Wooded gardens: adaptation to a temperate climate

3. Benefits

Efficiency and Durability

Low maintenance: By creating a mature edible landscape that imitates the climax stage of an ecosystem, we work with the forces of nature rather than against them. Using perennial plants saves considerable time and energy: there is no need to sow every year nor to work the soil, as their roots explore it in depth, finding moisture and minerals where annuals are unable to thrive. Because this edible vegetation remains in place throughout the entire year (and for many years), it provides a stable refuge for associated fauna and fungi. Finally, as the soil is constantly covered with ground-cover plants or organic matter, ruderal species (often considered weeds) cannot find suitable conditions to germinate. In an established food forest, weeding work—the gardener’s bane—is nearly nonexistent.

High productivity: A field of rapeseed captures only a minimal percentage of the sunlight it receives. Meanwhile, wooded landscapes use light optimally at every canopy layer. This performance results in higher biomass production and the creation of shaded and sunlit niches, hosting species with contrasting needs, even within small spaces.

This is why a well-designed forest garden is the agroecosystem that produces the highest amount of edible biomass per square metre.

Appendix 6. Source : Jardins-forêt, Fabrice Desjours

In conclusion

With nearly 8 billion humans on this Earth, continuing to consume animal products without the greatest restraint is akin to individual and collective suicide (read the National Geographic article). It is precisely at the moment when our denatured diet (which had its reasons for being at the time) jeopardizes the entire living tribe that the Universe provides the fruits of the entire planet on our shelves, as if to suggest to us that it is time to initiate a collective return to a predominantly plant-based diet. Isn’t life wonderfully well made? Thanks to agroforestry, we now have the techniques and knowledge necessary to establish productive forest gardens in our latitudes (probably with the help of some greenhouses and global warming) as our ancestors had already done in the Amazon. Isn’t it high time to put our intelligence to the service of life and to become what we have always been: gatherers living in the forest?

Now, if you wish to take action and participate in the reforestation of your country, you will find plenty of information in this book: